December. The shortest month of the year in my book. It comes in fast and goes by even faster.

But I knew we’d have to find time to have a class on gingerbread houses. We would make them from scratch, from start to finish. In a few hours.

Right.

The plan for the lesson: mix gingerbread dough, roll and cut out dough shapes, bake pieces, and finally, build and decorate houses.

Obviously we would have to fast track the process to fit in with time constraints, kid attention spans and patience levels.

This took a bit more prep on my part.

Namely, I made a triple batch of dough and used two-thirds of it to pre-bake the gingerbread house pieces that we would assemble in class.

(Small confession: I ate the trimmings from all 36 of them.)

The last third of the dough would be chilled and ready for the kids to roll out. I also made a double batch of royal icing.

Roll call. 5 kids. 3 moms. 1 dog. Commence baking class.

Gingerbread dough, just like most cookie doughs, is made by first “creaming” the fat with the sugar, blending the two together to make a, well, creamy mixture.

I explained to the kids, that in order to combine these two ingredients, the butter would need to be at room temperature; soft enough to stir together, but not melty or oily.

We plopped our stick of butter into the bowl and mashed it around with a wooden spoon to soften it a bit more.

The kids took turns adding the brown sugar, three kids, 1/4 cup apiece. We beat the two ingredients together until they were well combined.

We weren’t trying to incorporate a lot of air into the mix, but just trying to get it well blended.

“What do you think would happen to the butter if I added a cold ingredient to our bowl?”

We talked about how it would make the butter clump up, which might make it harder to combine with the rest of the ingredients.

“So it would be better to add a room temperature egg instead of a cold one?”

Affirmatives all around.

We finished mixing in our wet ingredients, then set them aside to concentrate on our dries, which they took turns whisking together in a separate bowl. After smelling all the spices, that is.

“Don’t inhale the clove!”

The last step was adding dry to wet.

“What do you guys think would happen if I dumped this whole bowl of flour into the wet ingredients and tried to mix them?”

Eyes from bowl to bowl.

kid 1: “Would it be hard to mix?”

kid 2: “You could mix in a little at a time.”

Three additions later, with the help of a bowl scraper, we had our gingerbread dough ready to be wrapped in cling film and placed in the refrigerator.

First I asked what kind of shapes they thought we would be making for our houses. They took a look at the already baked cookies.

“Rectangles!” “Squares!”

Me: “So should I form my dough into a big round ball?”

“A rectangle!”

I showed them how to use the plastic wrap to press the dough into a nice, flat rectangle.

I explained that the dough would be too soft and sticky to roll so it would need to chill for the butter to firm up, and for the flour to keep absorbing the liquid in the dough. For about 3 hours.

Concerned looks.

Aha! But I had dough ready for them to roll so we could proceed immediately.

Hurray!

A quick explanation of how to roll followed:

Parchment paper, a little flour on top of that, then the dough, a little more flour, and finally a second sheet of parchment paper.

Anchor an edge of the paper/dough “sandwich” against the side of the table with your body and start rolling.

The dough should roll nicely between the two sheets.

If it starts to stick, peel off the top sheet of paper, dust with a bit of flour and replace the parchment, then with both hands, one on each end of the paper/dough sandwich, flip the whole thing over.

Peel off the top sheet of paper, (formerly the bottom), dust with flour and continue until the dough is about 1/4″ thick.

They were more interested in cutting out the shapes, so we moved on.

They used a knife to trace the edges of the parchment paper patterns: one square side, one front/back, and one roof piece.

kid 1: “Wait, so we need two of each, right? Six pieces?”

yep.

kid 2: “It’s easier to cut them out if you line the sides up.”

yep again.

We removed any unnecessary bits surrounding the cutouts, slid the whole sheet of parchment onto the back of a the flattest sheet pan we had, and placed it into the oven.

They were anxious to decorate, but were curious about the gingerbread they could smell baking.

Me: “You get to eat that”

“Yay!”

Assorted candies, piping bags and bowls of royal icing, and spatulas were distributed around the table.

Royal icing designs they wanted to pipe on the house walls, and any candies they wanted to stick to that icing should be done first, I explained, before assembly. The roof pieces could be added last and decorated in place.

There was little hesitation to jump in.

While they were working on decorating, I pulled the gingerbread out of the oven, and while the cookies were still hot, used a sharp knife to trim and straighten the edges. This is super important as there is nothing more frustrating for a kid, (or adult for that matter!), than trying to fit wonky sided shapes together.

I had covered heavy, 6″ x 6″ cardboard squares with foil, which we would be building the houses on. I showed them how to spread a layer of icing on the square to act as a foundation for the walls.

I was a little worried that the younger kids, specifically mine, would get frustrated with assembling the houses. The royal icing acts like cement, but it does take a few minutes to set up enough to have the pieces stand on their own.

And too much icing creates a lot of slipping and sliding. A moderate amount is best.

There were lots of requests to “hold this please” and “can you help me with this wall?”, but I was pleasantly surprised to see that once they got the feel of it, they did great with the construction.

The small size of the houses allowed the process to go rather quickly. Larger houses would have required more drying time to be stable enough to continue decorating.

Roof pieces were added. More candy. A marshmallow snowman here, a red vine path there.

Finally, “I think I’m done! And I’d like to eat now.”

Me: “I have some leftover split pea soup.”

“Uh”

Warm gingerbread pieces are passed out to the kids who have had enough decorating.

Some decorate until the last possible moment.

My daughter: “But I’m not done yet!”

Me: “You live here. You can decorate all day if you want.”

At least for another hour.

We mixed this dough by hand, (I like the kids to be able to see the process), but it can certainly be done in a mixer, especially if you are making a larger batch. I doubled this recipe to make enough dough for six small houses. The walls measured 3″ x 3″, the front and back pieces were 3″ x 4 1/4″, and the roof pieces were 3″ x 2″. The scraps can be re-rolled and re-cut.

Gingerbread

4 oz unsalted butter, slightly softened (room temperature)

¾ c packed light brown sugar

¼ + ⅛ t salt

1 egg, room temperature

½ c dark molasses

½ t vanilla

2 ¾ c flour

2 t ground ginger

1 t cinnamon

½ t baking soda

¼ t cloves

Cream butter, sugar and salt together. Add the egg, then the molasses and vanilla. Set aside. Whisk the remaining ingredients together in a separate bowl, then stir them into the wet ingredients in three additions. Wrap dough in plastic and refrigerate for 3 hours or overnight.

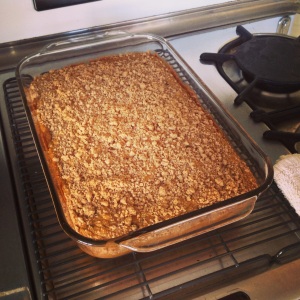

Roll dough between parchment, dusting with flour as necessary. Roll to ¼” thickness. Leaving the dough on the parchment sheet, use a parchment paper template to cut house shapes. Remove any scraps and slide the dough and parchment onto the back of a flat sheet pan. Bake in a preheated, 350 degree oven until gingerbread is firm and toasty, about 10 – 15 minutes. Use a sharp knife to trim still warm gingerbread pieces. Let cool completely.

Make plenty of royal icing! You can use ziploc bags to decorate with, but I prefer plastic piping bags and decorating tips with couplers, as the ziplocs tend to bust seams pretty easily. This will result in kid meltdown. If you have to use ziplocs, you might have better luck with the heavier freezer bags.